Eight key points in the outlook:

- Insolvencies remain high – “Australian businesses face ongoing challenges, with insolvencies reaching record numbers in 2024, though as a percentage of registered companies, levels are more moderate. Construction and Hospitality sectors remain the most impacted.”

- Macroeconomic pressures – “Rising prices, interest rates, and accumulated tax debts are major contributors to business failures. The cost-of-living crisis is also a cost-of-doing-business crisis, particularly for discretionary sectors.”

- ATO enforcement impact – “The Australian Tax Office’s return to normal debt collection post-COVID has surfaced pre-existing financial stress, contributing significantly to the rise in insolvencies.”

- Global economic uncertainty – “The Trump administration’s tariff regime adds significant unpredictability to global trade and financial markets, which will impact Australian businesses indirectly.”

- Trade and investment risks – “Proposed US tariffs are likely to slow global growth, lower US stock markets, and weaken the Australian dollar, affecting businesses reliant on international trade.”

- Slowdown in population growth – “Government policies reducing immigration and foreign student intake could weaken demand across key industries, adding to business pressures.”

- Credit conditions to remain tight – “CreditorWatch data on trade payment defaults and insolvency probabilities suggests ongoing business credit stress, though slight improvements were seen in late 2024. The extent of the US tariff impact will have a large effect on the ultimate outcome.”

- Interest rate outlook – “We are not expecting a cut next week, but the RBA may cut rates again in May 2025 if inflation continues to moderate, but large cuts are unlikely due to ongoing government fiscal support.”

The starting point for our 2025 outlook

When forecasting I often like to: 1) identify the starting point for the forecast (the factors that have combined to produce the current business conditions); and 2) consider the big forces that are likely to affect the outlook. This construct can usefully be used by any business.

Our launching point for the 2025 outlook sees the Australian economy coming off a record year of insolvencies by number of companies, but a more moderate year for insolvencies as a share of registered corporations (though still much higher than recent years). The trend has been steeply upwards over 2024, in part rebounding from reduced enforcement during the pandemic, and has been driven by insolvencies in the Construction and Hospitality sectors. It’s possible that the trend for insolvencies may have stabilised or even improved a little towards the end of the year, as the mid-year income tax cuts flowed more fully through the economy as several sectors have shown more favourable trends in recent months.

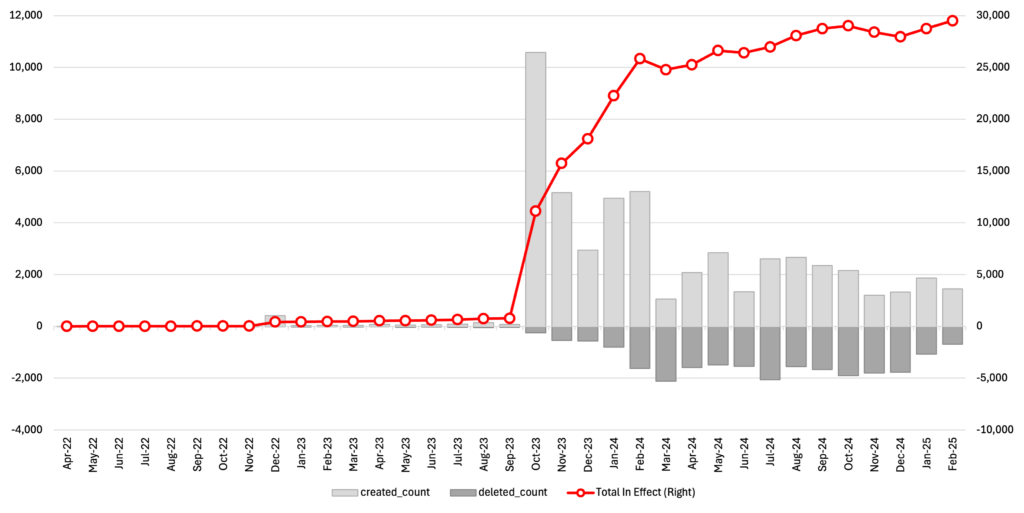

ASIC first time insolvencies

Monthly, seasonally adjusted

Data sources: CreditorWatch, ASIC database direct link, Macrobond

The rise in insolvencies is often attributed to the renewed collection activities of the ATO post-COVID. My view is that the ’hands off’ approach to collections by the ATO during the pandemic may have played some part in the build-up of tax debts, though the dominant issue was still the multi-faceted shocks the COVID pandemic and associated policy responses brought to many businesses. The recommencement of normal collections’ activities by the ATO has brought some of these underlying issues to the surface and this force remains important in the outlook.

The macroeconomic and business environment remains the biggest external cause of business failure. While the economy has been returning to normal since early 2022, there remain many pressures on businesses from the very complex set of circumstances and after-effects brought about by the COVID pandemic.

The rise in prices and interest rates has been particularly important. Whenever businesses (or consumers) experience very large changes in prices (either up or down) over a short period, it tends to lead to significant challenges. The cost-of-living crisis should also be thought of as a cost of doing business crisis for many firms. Discretionary businesses such as Hospitality have had to handle not only higher wages, insurance, rent, food and other input prices but have also had their customers battling similar cost pressures.

Importantly, if the RBA is successful in returning trimmed mean inflation to 2.5% in the second half of 2026, for the most part, this does not mean prices have fallen or the cost of living or of doing business has declined. Indeed, this measure of underlying consumer price rises will have risen about 25% in six years.

Trimmed mean CPI – Australia

Index: Q2 2008 = 100

Data sources: CreditorWatch, Macrobond

The big forces affecting the outlook

The starting point analysis highlights the cost of living as a force that is expected to be an ongoing source of pressure for many businesses. Similarly, the accumulated tax debts of companies and ongoing enforcement activities of the ATO will also be acting to keep insolvency activity elevated. In the two charts below, it should be noted that the counts of tax defaults are for businesses with a tax default of over $100,000.

ATO tax defaults

Inflow, outflow and total in effect

Data sources: Australian Taxation Office Direct Link – Currently Active ATO Defaults and Inflow and Outflow

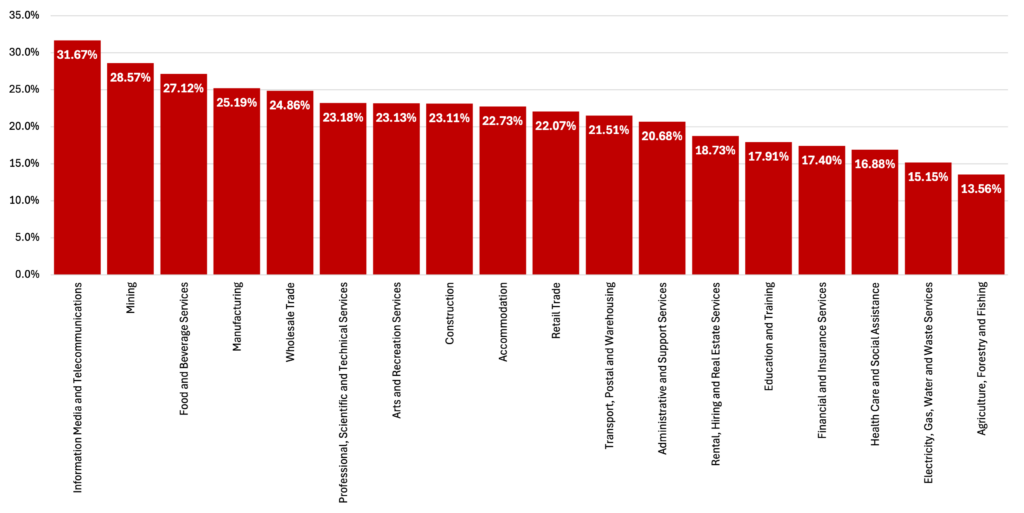

Insolvency given ATO default

12 months to February 2025

Data sources: Australian Taxation Office Direct Link – Currently Active ATO Defaults and Inflow and Outflow

What other big forces are out there? Looming large for businesses all over the world is the uncertainty associated with the policies of the second Trump administration. While much of the focus has rightly been on potential tariff plans, the administration has significant policy plans for trade, immigration, fiscal policy and regulation. By virtue of the US economy’s size and close financial market links across countries, these developments will be transmitted to the rest of the world.

The proposed, but not fully clear, tariff policies due to be announced on 2 April, present a significant downside risk to US and global growth. Because Australia is not a significant exporter to the US, the direct impacts of US tariff policies for the economy are likely to be relatively small, though not for the industries affected.

The indirect impacts are likely to be more significant via the impact on Australia’s major trading partners in Asia, via financial market channels including importantly the share market and via the subsidiaries of US companies operating in Australia.

A substantial increase in US tariffs can be expected to slow global growth, raise US prices and lower US share markets. It’s unlikely that the Australian government will respond with reciprocal tariffs, meaning Australian businesses and consumers won’t be paying more for imported goods due to tariffs, though the uncertainty over global growth and likely resultant lower prices for our export commodities may well keep the $A low.

Additionally, changes to supply chains, if tariffs are sustained, might also keep shipping costs high as trade redirects around the globe, while some of that redirected trade may find its way into Australia’s markets at reduced prices, which would be good for consumers, but not for local businesses competing with the tariffed goods.

The current uncertainty will also make it hard for boards and businesses to consider investment, while the new rules remain unclear. Even once clarified, it’s not impossible to imagine the risk that the President may at some stage completely change his mind and reverse his policies. US economic policy changes are therefore a third large force to keep abreast of. These are likely to be a negative for growth and thus will act to raise credit and insolvency risks in general.

Slower population growth due to the government’s policy changes to immigration and foreign students are also expected to be significant.

How best to keep across developments

With so many conflicting pressures on businesses, it might seem hard to see the wood from the trees. From a macro perspective, I continue to rely on the signals of the SEEK Job Advertisements series and the NAB Business Survey as great aggregate indicators of how the Australian economy is performing.

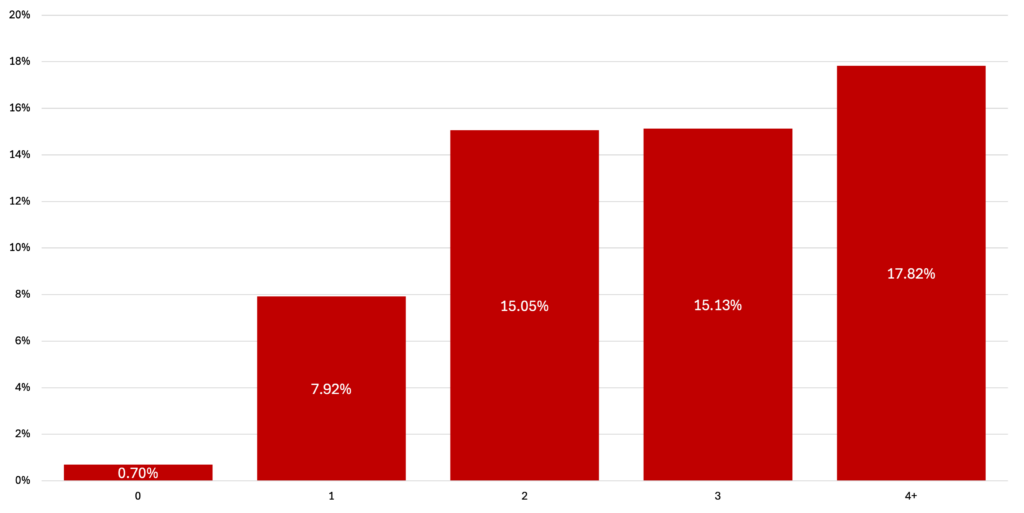

From a credit perspective, the CreditorWatch proprietary series on trade payment defaults is extremely useful. A trade payment default occurs when a business lodges a default notice against another business not paying an invoice. The probability of insolvency rises significantly to the extent that multiple businesses report that a counterparty is not paying its invoices.

Insolvency rate by number of payment default claimants

12 months to February 2025

Data Sources: CreditorWatch Trade Payment default data (lodged defaults), ASIC documents

Trade payment defaults improved a little in late 2024 and early 2025, consistent with slightly improved macroeconomic data as the mid-2024 income tax cuts flowed more broadly through the economy. The RBA’s February interest rate cut is likely another favourable development, though needs to be followed up with a few further cuts given the other pressures facing businesses. CreditorWatch’s overall impression is that business and credit conditions will remain challenging in 2025.

Trade Payment Defaults

Monthly, seasonally adjusted, Feb 2020 = 100

Data Sources: CreditorWatch Trade Payment default data (lodged defaults), ASIC documents

The interest rate outlook

In total, this continues to leave me relaxed that inflation is tracking back towards the 2.5% mid-point target of the RBA, which is what the Board was signalling it wanted greater confidence about before cutting interest rates in February.

We have the separate Monetary Policy Board taking over monetary policy setting on 1 April, when each member will get a vote and unattributed votes will be published. Market pricing does not have the next interest rate cut fully discounted until July, however, I still expect the Board to make another modest reduction in rates at the May Board meeting, provided the Q1 CPI released in late April prints a trimmed mean of (preferably) 0.6% q/q or 0.7% q/q.

The need for larger cuts isn’t particularly there at present, with the Government playing a strong supporting role for growth with fiscal policy in the budget released overnight, though it remains to be seen how much of the policy promises are enacted as this will depend on the May election outcome.

The scale and breadth of Mr Trump’s tariffs will hopefully become clearer on April 2. Directly these won’t be large for the Australian economy but will affect several industries. The risk is indirect if there are large broad-based tariffs and reciprocal tariff action on Australia’s Asian trading partners and on Europe.

The monthly CPI release for February showed annual headline CPI dropping from 2.5% to 2.4%, but the more important (from a monetary policy perspective) trimmed mean and ex volatiles and holiday travel measures were still a little higher at 2.7% y/y (though both a little lower from January, when rates of 2.8% y/y and 2.9% y/y where recorded). That’s not too far above the RBA’s target in the scheme of things.

Subscribe for free here to receive the monthly Business Risk Index results in your inbox on the morning of release. No spam.

Get started with CreditorWatch today

Take your credit management to the next level with a 14-day free trial.